A Rhapsody on Artificial Intelligence & Art

With a detour through the Italian Renaissance, Protestant Reformation, and a Japanese garden

Not that long ago, art created with artificial intelligence was an abstraction, a hypothetical concept that may come about in the future, but had no real consequence in the moment. That’s not the case anymore. I use “art” here broadly to include books, paintings, music and anything conventionally associated with creative expression. I noticed recently that AI art had entered my little world without me even realizing it, and started thinking about what exactly it says about our society.

I listen to a lot of instrumental music. I love what we in the West colloquially call “classical music,” but I also like things like Indigenous American woodwind music, the beautiful sound of the traditional Chinese Erhu and tranquil Japanese shakuhachi, a type of bamboo flute.

I’ve studied Western classical informally, but I don’t really know anything about these other forms—except that when I hear it, I really like it. Before the internet, it would have been difficult to discover or find shakuhachi. I suppose they would have sold this type of music at CD shops or maybe had it at libraries. I don’t know. But I know that on Spotify, I can type in almost any combination of words in the English language and there’s a playlist for that. These playlists serve as a kind of curriculum. They often feature artists who I can learn more about. It’s how I discovered, for example, Hong Ting and Lei Qiang, who are both accomplished Chinese musicians.

Recently, however, I encountered something a bit different. There’s a Spotify playlist titled “Japanese Garden” and it’s described as “A peaceful place with the traditional sounds of Japan.” Good start. One track named “Zen” caught my attention because it sounded a bit unusual. The artist goes by Paco and describes himself as “a recording artist who produces music for fun. He uses innovative artificial intelligence technologies for composition, as well as state-of-the-art voice synthesis engines.”

I was a bit dismayed, although I couldn’t pinpoint exactly why. I did find the track relaxing. But I also felt betrayed. The playlist—created by Spotify itself—had said “traditional sounds of Japan,” which to me excludes anything that uses AI or synthesis. The more I thought about it, the more I realized I didn’t have any issue with Paco. My issue was with Spotify for making and curating this playlist in the first place. How many thousands of artists exist on Spotify who are making traditional Japanese music and aren’t being boosted or promoted at all? Then I came across some folks on Twitter who had far more substantive issues with AI in art—some with Spotify, some elsewhere.

Ted Gioia is a music critic and historian who specializes in jazz. He wrote about the problem of mysterious artists on Spotify in a recent essay,

“I’m especially alarmed by those strange playlists—filled with mysterious artists who may not really exist, or almost identical tracks circulating under dozens of different names.

“Here’s a new example—a 20 hour playlist called “Jazz for Reading.”

“I’m supposed to be a jazz expert. So why haven’t I heard of these artists? And why is it so hard to find photos of these musicians online?”

“I listened to twenty different tracks. There’s some superficial variety in the music, but each track I heard had the same piano tone and touch. Even the reverb sounds the same.”

I’ve come across the playlist Gioia mentioned, and while not a music historian, I had a similar thought. A 20-hour jazz playlist and not ONE thing from Miles Davis? Zero tracks from Dave Brubeck? Charlie Parker? Thelonius Monk? John Coltraine, Billie Holiday, Jon Batiste? How in the world is that possible?

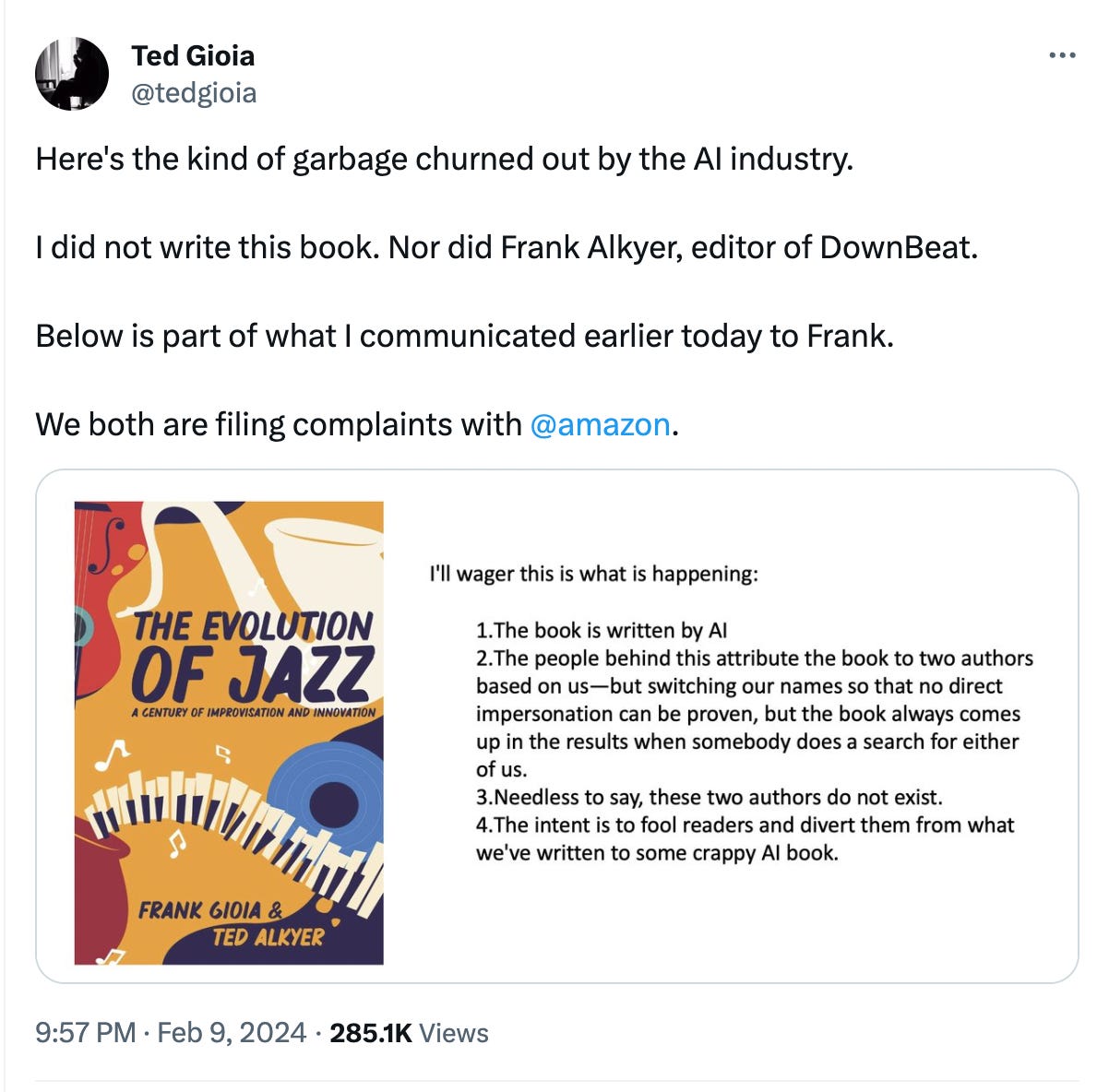

But for Gioia it gets a bit worse.

So what the hell’s going on here? Paco, from what I can tell, is a real person. He has a personal website and he is using AI to make music. I don’t know how I feel about using AI to make “traditional” music. But that is still qualitatively different from what seems to be going on with some of these other creators. It’s often not clear the artists even exist and are churning out milquetoast garbage, which Spotify is then promoting. The fake book issue on Amazon takes things to another level. (Ironically, there is at least one real Frank Gioia out there: He was a mafia enforcer turned informant.)

There are many other tracks on the “Japanese Garden” playlist by artists who have no bio and seemingly do not exist online. Same on the Jazz playlist. One name in particular stood out: Uno Blanket. Now there very well could be an Uno Blanket out there, but all I could find were some tracks on iTunes. No personal website, no social media, nothing. Yet Blanket has 121,426 monthly Spotify listeners and is featured on multiple Spotify playlists.

This is not merely about gatekeeping in the art world, which is a problem on its own. The world is constantly changing, and art is no different. When the piano was first invented, Johann Sebastian Bach wasn’t a big fan. But when was the last time you met anyone who owned a harpsichord? Auto-Tune (a kind of AI!) was derided and now it’s everywhere. Eminem once rapped that nobody listened to techno. Now electronic dance music (EDM) is a massively popular form of music. Last August marked the 50th anniversary of what many consider to be the “birth of hip hop,” which introduced the world to a new form of music: scratching records. And these are just examples of how music has evolved. I mention all of this just to make the point that I don’t think AI is “bad” in the abstract. Very few things, if any, are just flat out bad. It’s how they are used. And the manner in which things are used directly correlates to the environment in which they exist. Returning to my initial question: What exactly does the rise of AI and the way it's being used say about our current society?

The music historian, composer, and pianist Robert Greenberg has a phrase that he’s developed into an entire course: Music as a mirror of history. He describes the premise of the course (which I’ve taken) like so:

“Despite the abstractness and the universality of music—and our habit of listening to it divorced from any historical context—music is a “mirror” of the historical setting in which it was created, and certain works of music do not just mirror the general spirit of their time and place, but even explicitly evoke specific historical events.”

Without getting into the nitty gritty, one of Greenberg’s examples is how music in Italy and Germany developed along different paths, and how much of that has to do with things that may seem to have nothing to do with music, such as the influence of the Catholic church in Italy (the medieval Church thought instruments were blasphemous) and the Protestant Reformation in Germany (Martin Luther was convinced instrumental music could honor God). What are the effects of this? Well, for one, Italy became the capital of melodic vocal music whereas German music focused more on instrumental harmonies. I’m glossing over a lot here, such as the difference in the Italian and German languages and how that factors in, but the point is, the cultural environment directly affected what was being created.

As I said above, I’m encountering music that without Spotify, I’d probably never hear. So that is good! But that gives Spotify immense power and influence over what gets heard. We’ve seen dynamics like this in the past. There were the infamous payola dynamics that dominated distribution in the first half of the 20th century. If you want to go wayyyy back, some historians consider the Medici family the greatest art patrons of all time, even suggesting that the entire Renaissance aesthetic could be traced back to the tastes of one man, Cosimo de’ Medici. Lorenzo—Cosimo’s grandson—said the family had spent close to $500 million (adjusted for inflation) on art by the time he took over. And the family would be the de facto rulers of Florence for another 300 years!

The Medici, however, were not interested in monetizing the art they funded. They wanted to project power and piety. Millions of people all over the world travel far and wide to see works by Da Vinci, Michelangelo and others because of their brilliance. And they are brilliant. They just aren’t devoid of context. Cosimo was deeply pious, they say. He was also a tyrant.

Art using AI is going to become more common. Maybe not right away, but I have a hard time believing it will just die out or go away. But as David Graber once said, “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.” We can decide if artificial intelligence is used to enrich our understanding of the human experience. We don’t have to leave it up to chance. The reason you don’t hear about payola anymore is because we made laws to deal with it. AI can be a tool that lets us create new and innovative artistic expression, or it can be used as a shortcut to make monetizable trash. Unfortunately, I’m worried that our profit-focused world funnels things toward the latter.

We’ve already seen companies like Universal take action against AI companies scraping their music from the internet to be used without their consent. They asked Spotify and Apple to block lyric scraping. The use of AI was also a major sticking point in the negotiations between both the Writers Guild of America (WGA), Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), and film producers.

From CNBC on the WGA deal:

The WGA agreement established that AI cannot be used to undermine a writer’s credit or be used as a means to reduce a writer’s compensation. The contract does, however, leave room for studios to train AI using preexisting material. WGA’s original May proposal, which triggered the strike, would have disallowed studios from using any materials to train AI outright.

So in theory, studios could create entire shows without human writers, using AI to write the material.

Technology is agnostic. The people who control technology are subject to the influences of the culture within which they exist. So long as there is an assumption that sales or revenue are interchangeable with “good,” we should be wary of how AI will be used, even for art. And while most people may not actually believe that sales = good, that is how a profit-oriented capitalistic society functions. Can’t lose sight of that.