This description of Frankenstein is likely familiar to you:

“‘It’s alive!’ Dr. Frankenstein cried as his creation stirred to life. But the creature had a life of its own, eventually escaping its creator’s control.”

The problem is, in Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, Dr. Victor Frankenstein never makes that infamous exclamation, nor would it be accurate to say that the creature “escapes its creator’s control.” What actually happens is far darker, a more stringent indictment of human society.

There is little doubt that Shelley set out to write a story about the ghastly consequences sure to result from anyone attempting to play God and create life. She says so herself in an introduction to the novel. So it makes sense that the novel is a frame story in which Dr. Frankenstein is relating his story to another scientist in the hopes he will not make the same mistakes as he did—blind devotion to scientific achievement. But there’s another, even more applicable, reading of the story that deals with the way in which human contentment requires support from our social environments.

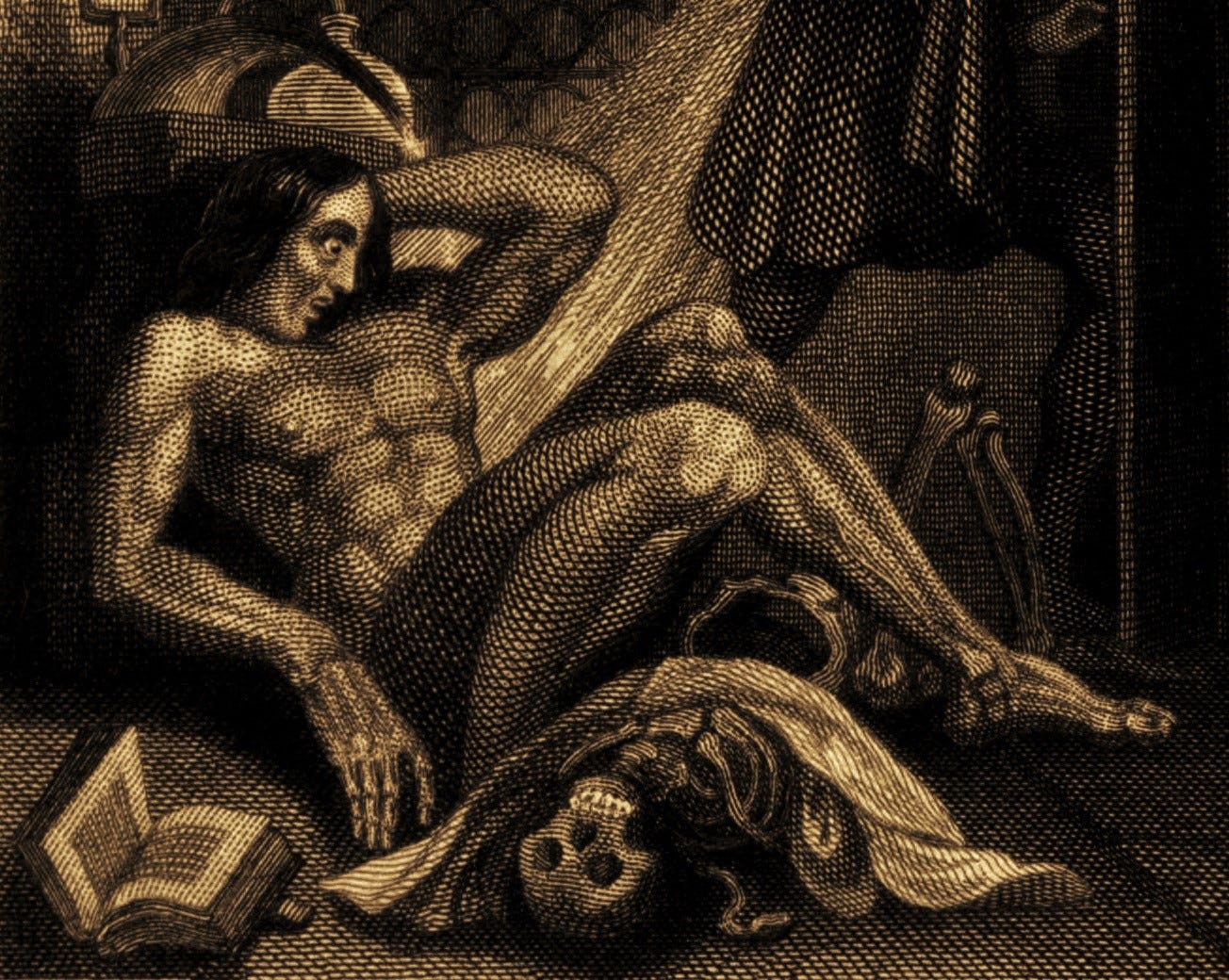

Dr. Frankenstein was obsessed with “natural philosophy,” or what we’d call science. His object in life was to push further than any other scientist had pushed before—to create life. However, when he succeeds, when the creature comes to life, he is immediately repulsed and regretful.

The first action of this “monster” is to sit up and smile. But Frankenstein cannot see past the grotesque appearance of his progeny and leaves the laboratory in hopes that the monster will flee. Hardly “escaping its creator's control.”

Dr. Frankenstein later learns that his much younger brother has been murdered. He pieces together that his creation must be who actually did this, an example of its wretched, irredeemable nature. When Dr. Frankenstein later encounters the “fiend,” as he calls him, he immediately demands an explanation for why he killed the child.

“I expected this reception,” the monster says. “All men hate the wretched, how then must I be hated, who am miserable beyond all living things. Yet you, my creator detest and spurn me, thy creature, to who thou art bound by ties only dissoluble by the annihilation of one of us. You purpose to kill me.”

So begins the aspect of the novel I didn’t expect. It’s an allegory about the people we neglect who then harden and grow callous and vindictive. Instead of identifying ourselves as contributing to the wickedness, we pat ourselves on the back for having correctly identified a monster.

Dr. Frankenstein abandoned, essentially, an 8-foot-tall child with superhuman strength and an immense capacity for learning. In the time since fleeing the laboratory, the monster tried to befriend humans several times, each time being met with violence. He wandered into a village and the villagers tried to kill him. He came across a woman drowning in a river, saved her, and was rewarded by being shot by a hunter who assumed he was on the attack.

Most of what the creature learns about human nature comes from surreptitiously studying a family while he hides in an adjacent hut. Through observation, he learns language and how to read. He gains an understanding of what makes them happy and what troubles them. He tries to alleviate their struggles by helping them without being detected—gathering food, chopping firewood, shoveling paths. Ultimately, he comes out of hiding and attempts to befriend them, but he is beaten and chased away.

Frankenstein resolves that his only hope is to befriend a human child who has not yet learned prejudice. But upon encountering a young boy, the boy yells and recoils in fear. The boy, unbeknownst to him, makes a critical error and says that his father is an important person named “Frankenstein.” The creature kills the child, vowing revenge against his creator who has forsaken him, and against mankind generally.

Perhaps the most applicable lesson he learns is the importance humans place on appearance. The only person he has any success conversing with at all is blind. When he learns to read, he laments the fact that God made man in his image, but he was not made in his creator’s image. He assumed a child would be more gentle to him because a child wouldn’t have learned prejudice. He talks about how seeing nobody else and knowing nobody else who resembles him whatsoever adds to his feeling of loneliness and isolation.

When he meets Dr. Frankenstein again, he has a proposition. He asks if the doctor will create another creature, a woman monster who—in his own words— was as ugly and deformed as himself. Together, they will leave the world of mankind and roam the wilds of South America. Dr. Frankenstein goes back and forth on this. He has some sympathy for his creation, but he also fears that two monsters would be even more dangerous to the world. Dr. Frankenstein agrees, but after departing decides he can’t create a partner for the monster. So the monster systematically kills everything and everyone Dr. Frankenstein loves, vowing revenge against his creator.

From “infancy”, the so-called Monster of Frankenstein was made to believe he did not belong and that he was wretched. He asks the same questions we all ask: “Who was I? What was I? Whence did I come? What was my destination?” He had an intrinsic desire to learn more about the world and to help people. He wanted friends and family. He spends his time lamenting the fact his own creator hated him and that everyone else hates him too. He knows of no other beings like him. He is completely alone. It was the treatment by humans that made him a “monster.”

At the time Frankenstein was written, there was little understanding of human development. During the Industrial Revolution, it would be fair to characterize children as mostly burdensome. Despite a ban on abortion, church leaders were lenient on “infanticide” because a dead child was better than a dependent. Infant mortality was extraordinarily high, approaching one in three. In 1750, 33% of all Parisian children were abandoned on doorsteps. Anyone who has read any Dickens whatsoever can speak to the view of children in the Victorian years: little creatures born wicked who required harsh treatment to become good, productive members of society.

At the heart of these attitudes toward children is the state of human nature. Are we born wild and wicked? Or are we born as a blank slate—tabula rasa, as John Locke supposed—upon which societal contexts etch our personality? Shelley’s novel, and lots of modern research, suggests that we are neither. Instead, we are born with certain innate propensities, and the degree to which we find support from the myriad social contexts in our lives heavily influence who we become.

In a letter to Dr. Frankenstein from his adopted cousin, Shelley seems to acknowledge the way in which a society's institutions, which arise in relation to a society’s shared values, directly influence the wellbeing and growth of its citizenry.

“...the republican institutions of our country (Switzerland) have produced simpler and happier manners than those which prevail in the great monarchies that surround it. Hence there is less distinction between the several classes if its inhabitants; and the lower orders, being neither so poor nor so despised, their manners are more refined and moral. A servant in Geneva does not mean the same thing as a servant in England. Justine, thus received in our family, learned the duties of a servant; a condition which in our fortunate country, does not include the idea of ignorance, and sacrifice of the dignity of a human being.”

In other words, England cares less about the lower classes so they become mean and bad. Switzerland does care and invests more in their wellbeing, so they are happy. (It’s worth noting that when this was written, Americans still owned slaves, let alone servants). She discusses humans as having a functional property—those in Switzerland are more gentle and well-mannered, not because they are Swiss but because of how the Swiss treat people. The servants in England are miserable because they are treated miserably. An especially interesting inclusion given that Shelley wrote the novel while on an extended trip to Geneva.

After reading Frankenstein, I entered a dark hole reflecting on generations of humans—literally hundreds of millions of people all over the world—who, for whatever reason, were treated with contempt as children. Or even adolescents or adults, who hardened and grew callous toward humanity as a direct result of this wanton disregard for their well being. They then grow and have children of their own who are raised under the specter of human malice learned by their parents. And the cycle continues until somehow, someone breaks it through an act of human empathy and understanding.

The “hideousness” of Dr. Frankenstein’s creation can represent the depravity of perverting the natural order of things. But it’s also symbolic of how we can “other” people and base our treatment of people based on their appearance or other characteristics that are unfamiliar to us. We’re very good at devising explanations for why a set of traits is sufficient grounds for exclusion or that someone isn’t deserving of support.

Where does the responsibility for an individual’s wellbeing lie? Certainly, some of it rests with parents. Some of it rests with the individual. But does it not ultimately lie with the society in which this individual lives? Is it not also to the benefit of the society itself to put in place institutions to ensure that we are not creating Frankenstein’s monster?

When we insufficiently fund schools and fail to nurture the innate desire to learn, we are contributing to this creation. When we toss people in prison out of a misguided sense of retribution instead of making an attempt at rehabilitation, we are contributing to this creation. When we say that in order to curb inflation we have to cause a recession, which inevitably puts people out of work, resulting in incalculable human suffering, we are contributing to this creation. When we over-value individual “freedom” over the wellbeing of our fellow humans, we are contributing to this creation.

Some say Frankenstein is a quintessential teenage novel about belonging and acceptance. (Shelley, amazingly, wrote it when she was 18). Others latch on to the existential human questions—who are we? Why are we here? What is death? These are all fair interpretations but in my opinion, it’s most interesting to explore how Frankenstein’s monster is treated and the effect it has on him.

Frankenstein’s creature isn’t a monster when he awakes in the lab. He’s transformed into one by the people he encounters, beginning with Dr. Frankenstein himself.