This is an essay about Nightmare Alley. It’s not a review, but a vehicle to discuss things it made me think about. There are MASSIVE SPOILERS. If you plan on watching the film & don’t want to be spoiled, maybe come back to this essay later. On the other hand, having seen the film is NOT a prerequisite for understanding this essay. At least, it shouldn’t be if I did what I set out to do. I hope you enjoy it.

Here at Rhapsody, we…or rather, I am obsessed with understanding the human condition. I’m especially interested in motivation, because it’s the precursor to behavior: What makes people do stuff? What’s the relationship between individual motivation and the surrounding environment? Coercion is a kind of motivation that leads to certain kinds of behavior; support and encouragement are kinds of motivation that lead to other kinds of behavior.

Guillermo Del Toro’s Nightmare Alley is a movie about the human condition. It’s also about motivation, and it’s also about harnessing an individual's motivation to bring about desired outcomes. It’s about Stanton Carlisle (played by Bradley Cooper), a man who seeks to escape his past by joining a traveling carnival where he masters the art of mentalism—where a performer appears to have supernatural or extremely attuned observational skills, such as the ability to read minds or divine personal history. Carlisle, a charismatic showman, quickly realizes that with his natural showmanship, his aptitude for mentalism, and his new love, Molly (Rooney Mara), he can be more famous and more successful without the carnival.

Carlisle, it turns out, is an exceptional mentalist. He has a gift for reading people. It’s alluded to throughout the film that his skill in part stems from a poor childhood—he had to be good at reading people to survive. Throughout the film, we get breadcrumbs about his past, specifically his childhood. In the very first scene of the film, we see Carlisle interring a body in the floor of a house, which is then lit on fire. We eventually find out that man was his father, and that Carlisle hated him because he was a religious hypocrite and an alcoholic. His mother left his father for another man, and Carlisle blames his dad for letting this happen. Carlisle was molded by these events. They are his reason for joining the carnival troupe and the reason he’s skilled as a mentalist.

To succeed as a mentalist, you have to understand how to manipulate people so they believe that you, the seer, have supernatural powers1. Psychics and mind readers and mentalists and mediums wouldn’t be able to do their jobs if there weren’t some fundamental truths about all people that allow for generalized assumptions. Take the phenomenon psychologists call the Barnum Effect, which is that people tend to think personality descriptions apply specifically to them when they are actually vague and general. That belief is a behavior, but what’s the motivation? Why do people want to believe this? And what does it tell us about people generally?

The film is full of messages, both implicit and explicit, about motivation and behavior. The first comes to us from a carnival barker (the people who yell things like “step right up ladies and gents”) named Clem Hoately (Willem Dafoe), who runs the geek shows. A geek show is arguably one of the lowest forms of human entertainment ever devised. It includes either an alcoholic, a drug addict, or an alcoholic drug addict, who is so desperate for a fix they will do anything—including eat live chickens for an audience. To the paying audience, Hoately says, “Step right up and behold one of the unexplained mysteries of the universe. Is he man or beast?” But Hoately knows the real reason people show up: “Folks’ll pay good money just to make ‘emselves feel better. Look down on this fucker grind some chicken gristle.”

Carlisle’s mentor of sorts, Pete (David Strathairn) explains that mentalists, reading people—clairvoyance in general—works because “people are desperate to tell you who they are, desperate to be seen.”

Carlisle, when laying out his rationale for leaving the traveling carnival to Molly, says, “All of my life I’ve been looking for something—something I’d be good at—and I think I found it, Molly. I think I’m ready.” Ready for what, exactly? Ready to go out into the world and be seen, to show people who he is, to show that he is good at something. And perhaps, most importantly, to make himself feel better about himself.

Carlisle and Molly do leave the troupe, and they are successful until Carlisle starts believing his own lies. See, Carlisle and Molly are actually recreating a two-person show that Carlisle learned from Pete, who along with his partner Zeena, devised an entire system to feed information to each other during a performance. Pete wrote the system down in a book and warned Carlisle that the book was dangerous and could be misused. When a mentalist starts to believe their own lies, believing their powers are real, then other people can get hurt. Pete calls it having “the shuteye.” Carlisle doesn’t share Pete’s concern. He rationalizes this by saying that if you tell someone a lie, but it gives them hope, then it’s okay. Failing to heed Pete’s warning, Carlisle gets the shuteye.

During one show, a psychologist named Lilith Ritter (Cate Blanchett) is in the audience and is aware of the game Molly and Carlisle are playing. Typically, Carlisle is blindfolded and Molly feeds him information using coded language. But Ritter is on to the game. She says to Molly that she wants Carlisle to ask her questions rather than Molly. Ritter asks Carlisle what’s in her purse. Astonishingly, Carlisle correctly guesses a small pistol and describes the handle. Carlisle goes too far, though, and humiliates Ritter, unwittingly laying the seeds of his own demise. The two form a partnership where Ritter gives Carlisle information about certain clients that he can use to fool people. But later, when Carlisle runs into trouble as one victim catches on to his bullshit, Ritter betrays him and reveals she just wanted payback.

Admittedly, Nightmare Alley was like catnip to me. We have a mentalist trying to read people for profit, we have a psychiatrist abusing her position to feel powerful, and we have all the gullible marks searching for human connection in all the wrong places. All the while, I’m trying to read them.

I’ve written before about intrinsic values that are associated with wellness (competence, relatedness, and autonomy) and extrinsic values that aren’t correlated with wellness (status, wealth, and beauty). Carlisle is endlessly focused on status and wealth—he even says nothing in the world matters but “dough”—and that leads to his demise. He finds happiness because he has found something he is good at (competence), but his cognitive orientation is towards status—he wants to be better than his dad, he wants to be better than Pete, he wants to be better than everyone. When he visits Ritter’s office, he tells her she’s running a scam just like he is, and that she isn’t as powerful as she thinks.

The irony of sitting there trying to “read” people while watching a film about a literal charlatan was not lost on me. I haven’t read any other reviews of the film, I haven’t read anything Del Toro has said about the film, and I haven’t read the book it was based on. I also haven’t watched the original film adaptation from the ‘40s, but I do know that in each version, Carlisle’s downfall hinges on meeting an actual psychologist. I wondered if that was a commentary on the profession, trying to equate a carnival trick with an academic discipline.

It’s interesting to me that there’s a psychologist in the story at all. When the novel by William Lindsay Gresham was published in 1946, psychology as a profession would still be quite young. It wasn’t until the late 1880s that psychology was even considered a discipline separate from philosophy. William James, often considered the father of American psychology, published The Principles of Psychology in 1890 and Will to Believe and Other Essays in 1897. A fellow by the name of Sigmund Freud grew in popularity in the early 20th century, and his psychoanalytic approach to studying patients is felt when Carlisle sits with Ritter in Nightmare Alley.

Most of what I’ve read about Gresham comes from the book Noir Fiction: Dark Highways by Paul Duncan, which suggests Gresham was a man, like Carlisle, running from his past and constantly trying to find something he was good at. He resented the fact that his family had nothing and was fascinated by anyone with money. His first marriage was to a wealthy woman, but upon returning home from the Spanish Civil War, his wife leaves him. Gresham tries to hang himself….but fails. The rope snaps, he falls and knocks himself out. When he came to, he decided to engage in psychoanalysis. From there, it seems he tried whatever he could to get his life together. He was searching not for the meaning of life, per se, but some way to understand life, a system that would explain it to him or help him navigate it. According to Duncan, at one point Gresham joined the Communist Party and changed his name to William Rafferty. He dabbled in Presbyterianism, Zen Buddhism, the I Ching, tarot cards, and even Scientology. He worked a ton of jobs, from salesman to writer to magician. He battled alcoholism and cheated on his second wife—who eventually left him for C.S. Lewis, of all people.

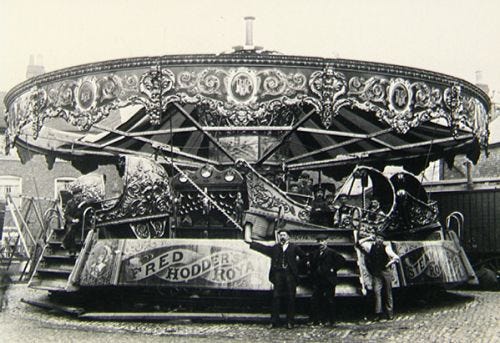

On some level, I think all artists and filmmakers are writing about the human condition. Singling out Nightmare Alley is strange in this regard. But there are some subjects that address it directly, not with a wink and a nod. Stories about traveling carnivals seem to fall into this direct category, though. While circuses have been around for hundreds and hundreds of years, these types of carnivals—not to be confused with the religious holiday popular in many countries, Carnival—are a distinctly American creation that emerged following the World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Whereas the World’s Fair had “anthropological” exhibits and demonstrated electricity, traveling carnivals had things like geek shows and bearded ladies. In the popular imagination, they are a refuge for outcasts and ne'er-do-wells. As Hoately says to Carlisle in Nightmare Alley, “Would a steady job be of interest to you, Young Buck? Folks here, they don’t make no nevermind who you are and what you done.

When Gresham’s family moved to New York City, so-called freak shows captured his attention. Specifically, according to Duncan, he discovered one of the “freaks,” a guy whose head was in his stomach, was just an Italian guy wearing a costume. In real life, his head was on his neck, and by performing the act, he could provide for a family of five. Later, while a soldier in the Spanish Civil War, Gresham learned about “carnie culture” and the idea of Nightmare Alley came to him. The economic insecurity and envy Gresham felt about his father and the Italian freak, respectively, are obvious in the way Carlisle resents his father and wants to climb economically. Carlisle’s search for something he is good at resembles Gresham’s never ending string of odd jobs.

At least in the movies, traveling carnivals shelter people with nowhere to go and entertain people who have little to feel good about. Whether or not that specific phenomenon mirrors real life exactly, the metaphor that institutions rise up because people need them is real. The world is full of forgotten and lost people as well as people looking for reasons to feel better about themselves. Society creates these situations through the choices it makes about who to support and how, through policies and cultural mores. Carnivals, Gresham, Gresham’s dad, the Italian, Carlisle, Hoately, Ritter—they are all a product of circumstances. That provides the foundation for their motivation, which leads to their behaviors.

Eventually, Carlisle’s scams backfire. He gets caught in a larger con by Ritter, who betrays him and takes all of his money—not because she needs it, but because she felt insulted that Carlisle said she wasn’t as powerful as she thought. He takes to drinking, succumbs to alcoholism2, and ultimately, he becomes a geek.

Gresham, Carlisle, you, me—we’re all looking for fulfillment. We need to feel like we are good at something and a part of something. When society doesn’t provide opportunities for those things, or even worse, reprograms us to think we need other things—more and more wealth, more and more fame—we break. Sometimes people find what they are good at but are so focused on fame and money that they lose what they’ve attained. Perhaps this is why Gresham was perpetually looking for a system or philosophy to tell him how to live. Gresham, unlike Carlisle, never found anything he was good at. "I sometimes think that if I have any real talent it is not literary but is a sheer talent for survival. I have survived three busted marriages, losing my boys, war, tuberculosis, Marxism, alcoholism, neurosis and years of freelance writing. Just too mean and ornery to kill, I guess,” he said.

We’re all searching for belonging and importance. But we also need security. That’s the commonality between us. Carlisle and Gresham both sought security they never had growing up, and it leads them to perverse places. It’s why we work in carnivals or attend geek shows, land in jobs we never wanted, do things we’re not proud of. It’s why we seek better, more prestigious employment. But these needs often stand in conflict with societal pressure, and this tension often breaks us until all we’re really trying to do is survive and find happiness. We never want to be the geek, but sometimes life convinces us that it’s our destiny.

Some readers may believe in the supernatural. This is probably not the essay for you.

I had originally written “becomes an alcoholic” but as one reader pointed one, that’s not really how alcoholism works. I think “succumbs to alcoholism” is a more accurate portrayal of alcoholism as a disease and not a decision.