How We Came to Need the Things We Need

It's the holiday season, which means we're buying a lot of stuff. An exploration to why we need so much stuff.

I need some new pans. Specifically a new sautè pan. The problem with buying a good pan is that I don’t know what makes a good pan. I don’t really know anything about different kinds of metal. I don’t know anything about durability or what kind of handle is good. I don’t know which brands can be trusted. I read that when assembling kitchenware, you should avoid buying entire sets of pots and pans and buy the products individually. That sounds like a lot of potential research.

So in 2021, what’s going to happen is I’m going to go online and read a recommendation guide at, say, Wirecutter or The Strategist, or I’m going to look up a well-known chef and see what they have to say about the matter. In either case, I’m trusting someone else, because I know that I’m out of my element here. What I am not going to do is buy a pan that I saw in an advertisement.

But, on some level, isn’t a well-known chef recommending a specific brand of pan kind of an advertisement? Properly speaking, it’s more of an endorsement. These days, what’s the difference between an endorsement and an advertisement? Maybe the difference is knowing if the endorser is being paid or not. But regardless, endorsements and influencers, ecommerce guides and product placement—those have become the contemporary way in which brands and companies reach us with most of their products. Often the ads don’t even make much sense, and not just in the “What the fuck is Matthew McConaughey talking about?” car commercials. Tom Brady1 is a pitchman for Subway and admits in the ad he doesn’t eat bread.

According to Merriam-Webster, the first known use of the term “influencer” was in 1662, but it was only added to the dictionary in 2019. There are two listed definitions, one more general:

one who exerts influence : a person who inspires or guides the actions of others

And one more specific, and for my money, the one most people have in mind when using the term:

a person who is able to generate interest in something (such as a consumer product) by posting about it on social media

Why do we need the things we need? Or more specifically, perhaps, why do we think we need the things we need? In a given holiday season, a person of very average means may give or receive more gifts, more things, than our not-so-distant ancestors owned in their entire life. Do I really need a specific pan for sautéing?

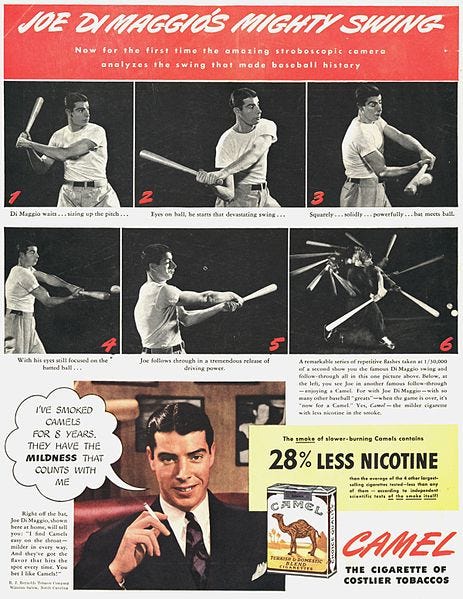

Advertising plays an enormous role in defining the things we think we need. And not only specific products, but lifestyle choices and behaviors. In the 20th century, advertising convinced millions that:

Any reader, I’m sure, could come up with another 1000 examples of not just products or services, but ideas, attitudes or perspectives that began as slick marketing and transformed into conventional wisdom. What they also could probably imagine is a number of things they now need, even though they lived a perfectly happy life before finding out they existed. And this would make sense because the birth of advertising as we know it, in the late 19th century, was less about companies competing with other companies to supply products for which there was high demand and more about creating demand for products of which they had high supply.

It used to be the case that people would go to their local dry-goods store or local market day and pick up what they needed if it was available. And those are just the items they couldn’t make themselves at home. Because products were being made from scratch and often by hand and were perishable, they’d haggle over prices based on the quality of the specific item. They’d form a pretty good relationship with the store owner.

That began to change in the 1880s, however, as large department stores such as Macy’s in New York City and Marshall Field & Co. in Chicago established themselves. With department stores came a number of innovations such as fixed pricing and the ability to return items, which allowed shoppers to purchase things they weren’t sure they really wanted.2

Advertising and other marketing techniques supercharged the consumer shift from general stores to department stores and catalog shopping over the next few decades. Although advertising and marketing weren’t new concepts, this kind of advertising—persuading consumers that they needed products they didn’t previously need or didn’t need to buy—was new.

There’s a fairly well-known story about a Heinz sales rep that may be apocryphal but does illustrate the shift that took place around the turn of the 20th century.

Sometime before 1911, an H. J. Heinz sales representative spent a week in a Wisconsin town promoting the company's vinegar. As Frederick W. Nash of the sales and advertising department told the story, no grocer in this community of about ten thousand stocked the product. Most bought vinegar from farmers and believed that their customers would not pay extra for vinegar with the Heinz label. The sales representative went from door to door in the best neighborhoods, collecting introductions from one woman to the next. He sold nothing, but offered taste tests and compared Heinz manufacturing techniques "with the crude and imperfect methods of farmers." If asked, he regretfully informed his hostess that Heinz vinegar was not for sale in her town. About fifty influential women telephoned their grocers to complain, and the sales representative left town with orders in hand

Now people could stop making their own vinegar or buying vinegar of varying quality at the store. They didn’t know they needed Heinz before, but Heinz knew they needed to sell a lot of vinegar because they could make a lot of vinegar. And they were selling it for more than what people were used to paying. We don’t eat a lot of chicken because people love chicken so much or because it’s incredibly nutritious. We eat a lot of chicken because the chicken industry figured out how to make a lot of chicken and then sold it to us in a million different ways. We don’t use gas stoves because they are better than electric ones, we use them because the gas lobby said they are better in cute little advertisements. De Beers just made an ad telling us that if we don’t spend two months' salary on a diamond, we must not love our partners very much.

Why do we need so much of the stuff we think we need? Because it was suggested we need it.

Now look, I’m not saying advertising is all bad. If there was no advertising, we wouldn’t know what existed. I’m also not a Buddhist monk who eschews all worldly possessions. I love clothes, I love books, I love stuff in general. I also love to buy stuff for other people. I reject altogether the idea that gift giving is silly because on economic terms, it has no value. Gift giving is a social activity with a myriad of psychological and societal benefits. I’m also not saying that companies such as Heinz did or do no good.

But what I am saying is that a lot of the stuff we think we need, we only need because companies—beginning with 19th century manufacturers up to 21st century tech companies—tell us we need it. There’s a line one can draw from cosmetics sold in a Parisian department store in the 1800s to Zuck’s metaverse—things we don’t need but are marketed to us until we do.

Let me now introduce John Broadus Watson who is notable for two reasons: First, he was a very influential 20th century psychologist who helped develop the psychological theories of behaviorism, which have been influential in marketing and advertising. Second, he is one of only two people I’m familiar with who have “Broadus” as a name, the other being Calvin Cordozar Broadus Jr., aka Snoop Dogg. Anyways, Watson worked in advertising himself. Ever had a “coffee break”? He is said to have popularized the idea in an ad for Maxwell House coffee. Watson and another psychologist, Walter D. Scott, applied psychological concepts to advertising and concluded that consumers were persuadable via direct command that played on their emotions.

"Man has been called the reasoning animal but he could with greater truthfulness be called the creature of suggestion. He is reasonable, but he is to a greater extent suggestible," Scott said.

I was talking to a friend recently about how it seems that consumerism is not only no longer taboo, but it’s kind of in? Brands are cool. Big studio films are three-hour-long product-placement videos. At least from my perspective, it didn’t seem like this when I was growing up in the ‘90s. Maybe I was just a kid but as my friend put it, “selling out” was the ultimate societal faux pax. Sure, there’s been product placement in movies and TV for a long time. These days, it’s more like the movies and films are just promotional vehicles for, I don’t know, let’s say, Transformers toys. Selling out is the objective. I’m not sure any movie or book has captured what I’m talking about quite as specifically and clearly as Chuck Pahulnik’s Fight Club:

“God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables, slaves with white collars, advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need.”

The problem is eventually the things we don’t need become so widespread that we do need them to participate fully in society. Yes, on an absolute level, I do not need an iPhone. But almost everyone I know has a smartphone, and so participating in contemporary society has come to require them—for both professionally and socially.. Same with a computer or any modern technology. We don’t need them in an abstract sense, and it’s unclear if they make us happier as a species, but wide adoption of technology makes it difficult to feel like you are a part of society without them. Businesses use advertising to create FOMO, and then the FOMO moves far beyond just fear—people get left behind entirely.

And again, I cannot state this in stronger terms: Most of this stuff is pushed on us not because there’s demand for it, but because the supply exists, and there’s profit to be made. Sure, smartphones have made our lives easier and more efficient in many ways. They are not wholly, entirely bad. But it’s an indisputable fact we did not need them when they were created, and there was no demand for them. There couldn’t have been; they were unknown to mankind. This formula is repeated again and again. The invisible hand often isn’t so invisible.

I’d probably be fine with just one pot and one pan. But there are many different kinds of pots and pans, and now that I know that, I want many different pots and pans. It was suggested to me that this was a better way, and I took their word for it. That’s often why we need the stuff we need.

I’m indebted to Professor Donald J. Harreld, formerly of BYU, and his course, An Economic History of the World since 1400 for some of the ideas I work through in this piece. The lectures acted as an excellent jumping off point for this essay.