Zero To Hero

Or, how the discovery, rejection, and eventual adoption of something most take for granted—the number zero—demonstrates the strange, slippery, and hard to grasp nature of "truth."

"What is Truth?" by Nikolai Ge, depicting John 18:38 in which Pilate asks Christ "What is truth?"Nikolai Ge, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During my final year at Ohio University, I took a course that I literally think about every day: The Philosophy of Cognitive Science, an examination of how humans understand and navigate the world we inhabit. It explored how our minds understand a three-dimensional environment, how the senses interact with each other—questions on the edge of the physical sciences. I think about it every day because it revealed how much of the world is a construct of some sort rather than an absolute truth. Some people hear color and see sound. Other species have an entirely different method of sensory perception, and therefore they experience the world differently than we do. Imagine if we had to use echolocation to move around or if we were attuned to the Earth’s magnetic field. The world would appear much different to us. It wouldn’t be correct to say we’d “see” the world differently, we’d just sense it differently.

My high-level takeaway from this course was that the truth is a lot more difficult to pin down than it seems. A lot of “truths” are evolutionary adaptations that help us to survive. It’s like we have been given filters through which we experience the world to help us get by, because without those filters, we can’t make sense of anything. And if the physical world that we literally sense isn’t quite what it seems, then what is?

It’s not an earth-shattering revelation that facts and truth are big topics these days. COVID-19 and the associated vaccines put this front and center. During the Trump presidency, the notion that we are in the “post-truth era” became a major talking point. At an even more abstract level, people like Elon Musk have popularized the theory that we may be living in a simulation1. The term “do your own research” has become a meme with associated Latin fallacy names such as argumentum ad Googlam and argumentum ad YouTube.

The internet has provided a way for just about anyone to find out information about almost anything. It’s also provided a platform for just about anyone to put information about anything out there for other people to find. This doesn’t just include isolated bits of information—let’s call these “facts”—but whole, prepackaged methods of interpreting facts. Anyone can hop on YouTube or even Substack, where I publish this newsletter, and acquire entire worldviews on any subject that exists.

Facts are not simple things, however. I used the word “interpret” with intentionality. As I’ll demonstrate in a bit, even the most seemingly mundane, bland “fact” is affected by cultural and institutional forces. There are systems of knowledge that require years and years of study to properly understand and contextualize. There's a good reason why it’s not advisable to represent yourself in a trial after reading a couple law books or operating on your dog after watching a few YouTube videos.

Unfortunately, our biology likes tricking us. The Dunning-Kruger effect is a term that emerged from research by Cornell University psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger and refers to overconfidence in one’s abilities2.

“Those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it,” they wrote.

Universal truths may exist, but as human beings we are stuck living in a world where prevailing opinion on a matter trumps truth. The notion of humans as perfectly rational is, of course, a myth. We evolved and adapted to survive, not seek out absolute truths. There’s an entire branch of philosophy dedicated to how we know what we know called epistemology, and it’s still going strong. Anyone who took an intro-level philosophy course is familiar with Socrates' famous experiment in which he takes a stick and inserts half of it into water. The stick looks bent. He takes it out, it is straight again. Which is true? The lesson: Our senses deceive us.

For many, that’s fine. We know our senses deceive us. But there are still facts. Math for example...right? Well, no. Even math is subject to societal and cultural forces. Take for example something that seems entirely beyond dispute: the existence of zero. Yes, the number zero, which falls between negative one and one. Zero.

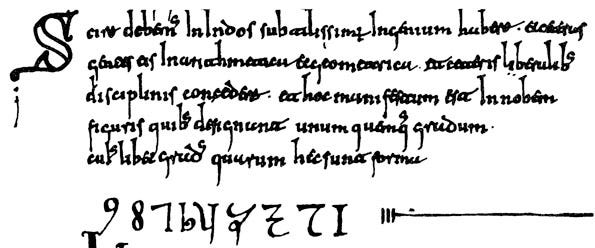

Zero (0) is not only a relatively recent discovery, but a highly disputed one. The earliest known use of zero as we think of it—meaning as an Arabic-style numeral3—was in 9th century India. The idea of zero had been around in the world for centuries by this point, but not in a script we’d recognize. Zero was discovered independently by the Maya and the Babylonians, though it’s believed the Babylonians were a bit earlier.

But it wouldn’t be until the Middle Ages that zero was widely used in Europe, and even then, merchants continued using Roman numerals, which have no zero in them. It cannot be represented. It wasn’t until the 16th century and the introduction of the Gregorian calendar that “0” would become commonplace. But the figure wasn’t entirely unknown for these hundreds of years, instead it was disputed and even banned for a time. How and why could a seemingly innocuous thing like the number zero earn a ban?

The first Arabic numerals in the West appeared in the Codex Albeldensis in Spain. The original uploader was Srnec at English Wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Because it was believed that the existence of “zero” threatened the existence of no less a personage than God him/her/itself.

Let me explain. The idea of “zero” is closely associated with the idea of “nothingness” or “a void.” In Aristotle’s Physics, he considered the possibility of zero, but ultimately rejected it under the principle ex nihilo nihil fit, which means that “out of nothing, nothing can come.” In other words, for Aristotle to accept zero means accepting the possibility that something could come from nothing. It leads to a logical contradiction4. It could not exist. If this is hard for you to understand, that is normal and fine and sort of underscores the point I’m making: Zero is so culturally accepted, such an obvious truth that it doesn’t even make sense for it not to exist. But it didn’t exist for most of human history.

Aristotle’s logic had profound implications on the Western world. In Catholic theology, a void or a time where there was “nothing” is also impossible because that supposes a time before God, meaning God isn’t eternal. He is not the alpha and the omega. This is obviously a huge issue!

Another issue lies with the numerals we are so familiar with today. Most people are aware we use Arabic numerals, but in the time of the Crusades, using “Muslim” numbers was a no-no5. In 1299, all Arabic numerals were officially banned in Florence. Zero, it was said, was a kind of gateway drug. I mean what comes next? Negative numbers. You know what negative numbers mean? Debt. You know how you get debt? Money lending. You know who frowned upon money lending? God. It says it right there in the Bible.

Psalm 15:5: Who does not put out his money at interest and does not take a bribe against the innocent. He who does these things shall never be moved.

Deuteronomy 23:19: “You shall not charge interest on loans to your brother, interest on money, interest on food, interest on anything that is lent for interest.

Exodus 22:25: “If you lend money to any of my people with you who is poor, you shall not be like a moneylender to him, and you shall not exact interest from him.

This inadvertently leads to a maybe obvious but noteworthy point: Zero is really important! Without zero, there’d be no Cartesian coordinate system, which means we’d have no calculus. In fact, we’d have no math at all beyond geometry. A lot of common, modern-day technology wouldn’t exist!

Theology—or more properly, cosmology—affects the discovery of zero in other, more subtle ways as well. Europeans and most of Western society generally view time as linear. There was a beginning and there will be an end and we exist somewhere in between these two points. But other cultures, such as the Maya and the religions that originated on the Indian subcontinent, do not view time as linear.

Why does this matter? A few reasons, some practical, some abstract. We’ll begin with the practical: How do we count? Most people start with one, not zero. This created a big kerfuffle around the turn of the millennium. Did the new millennium start in the year 2000 or 2001? Well, although the United States has no official calendar system, we use the Gregorian calendar, which is based on the birth of Jesus Christ. It declared the year he was born as year 1. The year before this was not “year 0,” it was 1 BC. There’s no year 0. Astronomers have their own calendar that has a year 0. Believe it or not, this is an ongoing debate. The Library of Congress does not recognize a year 0. The Royal Greenwich Observatory also says there is no year 06.

Now for the more abstract. The Maya thought time was cyclical. The religions of the Indian subcontinent also believe in a more cyclical cosmology. This is the basis for the way “0” looks: It’s a loop.

Nothingness is not just a familiar concept but a foundational principle of the Indian religions. The Maya, meanwhile, have an origin story that begins with a primordial void out of which life sprang. Something did come from nothing for the Maya. For them, it made perfect sense there was a zero.

Discussions about facts are challenging for a number of reasons, not the least of which is they invite bad faith interpretations and conclusions. Suggesting, for example, that facts have a societal, contextual component that affects their utility could be taken by some to mean there are no absolute truths and everything is relative. Let chaos and anarchy reign. As I sent this to my editor, I thought, “Is she going to think this is some antivax shit?” Because it isn’t at all. The point of this discussion is that absolute truths only get to us through filters. First, there’s our biology, our physical and cognitive makeup. And then things such as zero are subject to cultural forces and institutions. We all exist within a time and place and are exposed to overlapping cultural influences that shape how we view and interpret events. Those events are integrated into our personal model of the world, and then we ourselves act, and, in small, often imperceptible ways, modify the cultures and contexts that molded us. It’s a never ending feedback loop.

This may sound like abstract, philosophical gobbledygook. But when angry people show up ranting and raving about critical race theory at a school board meeting because they saw a post about it on Facebook, remember how zero was once banned in all of Florence because it was too closely associated with Islam. Remember the Dunning-Kruger effect. What people come to believe, and believe strongly, are absolute truths, are often not arrived at through sheer logic. Rather, they have been mediated through a number of cultural filters, such as religion and media, and psychological biases.

Perhaps our most profound challenge as humans is simply being honest with ourselves about what we know and why. Do we really know something to be a fact, or are we convincing ourselves of a truth because we need it to fit our model of the world?

Jean Piaget was an influential psychologist in the field of human development who suggested that everything we know and understand is filtered through our current frame of reference. In his view, we all have a mental model7 for how the world operates, and as we come in contact with new information, we either assimilate that information into our model (which he called a scheme) or we accommodate that information by changing our scheme to make sense of the new information. These are not strict processes, and there’s a bit of both going on. But here are some examples.

Have you heard a child misconjugate a word? They say things like “I heared” or “I eated” instead of “I heard” or “I ate.” This is a child applying their current scheme to words. They know that adding “-ed” means past tense, but haven’t yet learned that it doesn’t apply in all circumstances. They are assimilating new information. When they learn how to properly conjugate irregular verbs, it will be an example of accommodating.

Piaget’s view was that we are always on the hunt for equilibrium, or a state where all information is properly assimilated or accommodated.

Whether we like it or not, truth is contextual—not in an absolute sense, but certainly in a practical, social sense. If you’re in a group of ten people and the other nine people think the sky is made of turtles, the absolute truth doesn’t really matter. In this micro-world, the sky is made of turtles. When these turtle-sky people leave their turtle-sky world and venture into the real world, they aren’t just going to readily accept that the sky is not made of turtles, they are going to think everyone else is insane. In 2011, Eli Pariser coined the term “filter bubble” to describe the phenomenon of an individual becoming “intellectually isolated” as a result of the personalized nature of online search results.

We like to think of ourselves as being rational. Our beloved free-market system is based on rational actors. But we simply have a capacity for rational activity. We aren’t computers operating purely on logic. We decide things for all kinds of reasons, and for a long, long time, much of the world decided there was no zero, and that was that.

So what is the answer here? The answer surely isn’t, “Well, nobody can know anything without a PhD.” When I think about knowledge, the key is transparency. People explaining how they know what they know and why. It’s what’s so galling about the emergence of “do your own research” as a kind of debate-ender. The scientific method is effective, among other reasons, because it requires practitioners to show how they reached their conclusions so that others can attempt to replicate and confirm results. Quality journalism is painstakingly transparent. It shows the reader, listener or viewer where the information came from. Good history, biography, philosophy—they all cite sources so that their work can be interrogated, and, if necessary, modified and corrected. Transparency is critical. In fact, one of the primary issues with the algorithms used by internet platforms such as Google, YouTube and Facebook is that the algorithms they use to decide what users see is not transparent.

Another critical component is humility and empathy. There’s wisdom in knowing what you don’t know and admitting when you’re wrong. There’s wisdom in accepting that mistakes happen and that as new information is available, theories change. All anyone can ask for is a good-faith interpretation of the facts currently known. Admitting mistakes shouldn’t damage credibility, it should strengthen it. Hiding mistakes, misrepresenting information, willful omission of facts—this is what should damage credibility.

When I started Rhapsody, in my first essay, it was important to me that I point out I’m not an expert in basically any field I’ll be writing about, but that I’d be transparent about where I get my information. The objective is to learn and to improve. I try to take that same approach with everything I do in life. I try to give others the benefit of the doubt and assume they are acting in good faith until I have good reason to believe they are not. I’d encourage everyone to do the same, because facts and the truth are more complicated than they seem.

Musk’s comments, and those of others, largely stem from a paper published by the Swedish-born Oxford philosopher Nick Backstrom. The paper is laconically titled “Are you living in a computer simulation?” It’s worth reading if you’re even kinda-sorta interested in this stuff. It’s quite short.

Interestingly, the opposite of this form of cognitive bias would be imposter syndrome, which is the tendency to think you know less or are less competent than you really are.

We in the West call numbers Arabic numerals because they were introduced to Europeans by Arabic speakers. However, they are sometimes referred to as Hindu-Arabic numerals because the original symbols were developed by Indian mathematicians and adopted by Arabic speakers.

This is a complex subject that I don't think requires delving into too deeply here, but if you want to understand more about Aristotle's logical process, I recommend this paper.

Sadly, but perhaps not unsurprisingly, many people still think Arabic numerals should be banned! In a 2019 survey, 56% of respondents said Arabic numerals should not be taught in school, including 72% of Republicans and 40% of Democrats. Of course, I'd go out on a limb here and say that 100% of these people have no idea they have been using Arabic numerals their whole lives.

This article in The Atlantic from 1997 about the debates over when the new millennium actually began is low-key insane and I encourage you to read it. It encapsulates how weird the debate over “zero” still is in modern times. I wanted to specifically pull out this passage, which was too long to include in the body of my essay:

Kristen Lippincott, the director of the Millennium Project at the Old Royal Observatory, from whose geographic coordinates Greenwich Mean Time is measured (and the RGO's former home), insists that the RGO is an authority. She compares it to "authorities from previous ages who might cite Aristotle, Ptolemy, or Bede." In settling on 2001 and renouncing zero the RGO has made a significant break with its past and with geography. One of the RGO's most illustrious directors was the fifth astronomer royal, Nevil Maskelyne (1732-1811), who stated that a century begins on the 00 year. The Old Royal Observatory sits atop the prime meridian, also known as zero — not one — longitude.

Lippincott argues that the RGO's determination on when the day, and thus the century, begins is based on international law. According to the transcripts of the International Meridian Conference of 1884, legally the Universal Day does not begin until it is "mean midnight at the crosshairs of the Airy Transit Circle in the Old Royal Observatory."

For the sake of argument, let's accept the legal definition: the millennium begins on January 1, 2001, at Greenwich. Now, imagine yourself vacationing in Tonga, near the International Date Line, where it is twelve hours earlier than it is in Greenwich, on the night of December 31, 2000. At the stroke of midnight, as the schoolchildren light their coconut-sheath torches, your digital watch turns from December 31 to January 1, 2001. Happy New Year! Happy New Millennium! No. Because it's still noon on December 31 in Greenwich, the millennium hasn't started yet. Legally, it's still yesterday. And it will remain yesterday until noon Tonga time, all evidence to the contrary. In fact, in all twelve time zones east of Greenwich midnight will come sooner than at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, but it will stay yesterday until midnight Greenwich Mean Time. This may not be how the world turns, but it's the official position of the observatory.

On the East Coast of the United States, five hours behind Greenwich, the new millennium will start at 7:00 P.M. Those people who celebrate midnight in Times Square will be five hours late. Californians must celebrate the new millennium at 4:00 P.M., while stuck in rush-hour traffic. "I guess we're seeing the last vestiges of British imperialism," Klingshirn says.

Piaget's work spawned thousands of studies. He's often thought to have been at the forefront of what's called the "cognitive revolution" in the study of human development, which means an increased focus on internal rather than external factors. However, he was not infallible. For example, some question whether this model can actually be tested or if it's too metaphorical and abstract. But it's still useful as a thought experiment to understand human behavior.

Joey, did you just write an article filled with zero truth?